Clinical Pathology

I created these curated notes as part of my board review studying process. I thought they might be helpful for others preparing for similar exams or just looking to review clinical pathology concepts.

PART I: BLOOD BANKING AND TRANSFUSION MEDICINE

Transfusion medicine sits at the intersection of immunology, genetics, and clinical practice. Red blood cells carry hundreds of surface antigens capable of triggering immune responses, and the field developed largely from learning-often the hard way-which mismatches matter and why. This section covers the immunologic basis of blood groups, compatibility testing, component therapy, and transfusion reactions.

Chapter 1: The Immunological Basis of Blood Groups

1.1 What Are Blood Group Antigens?

Blood group antigens are molecules expressed on the surface of red blood cells that can be recognized as “foreign” by another individual’s immune system. These antigens fall into two major biochemical categories: carbohydrate antigens (like ABO) and protein antigens (like Rh, Kell, Duffy, and Kidd).

Understanding this distinction is crucial because it explains fundamental differences in how antibodies form against these antigens:

Carbohydrate antigens are found not only on red cells but throughout nature-on bacteria, plants, and food. Because of this environmental exposure, humans develop “naturally occurring” antibodies against carbohydrate antigens they lack, without ever being exposed to foreign red cells. This is why a type A person has anti-B antibodies from early childhood-they were exposed to B-like carbohydrate structures on gut bacteria and mounted an immune response.

Protein antigens, in contrast, require actual exposure to foreign red cells (through transfusion or pregnancy) before antibodies develop. A person who is Kell-negative will not have anti-Kell antibodies unless they have been previously sensitized.

1.2 The ABO Blood Group System: Foundation of Transfusion Medicine

The ABO system remains the most clinically important blood group system because ABO antibodies are: 1. Universally present when the corresponding antigen is absent 2. Capable of causing immediate, life-threatening intravascular hemolysis 3. Predominantly IgM, which efficiently activates complement

The Biochemistry of ABO

The ABO antigens are built upon a precursor structure called the H antigen. Think of the H antigen as a foundation upon which the A and B antigens are constructed. The H antigen itself is a carbohydrate chain with a terminal fucose residue, synthesized by the enzyme fucosyltransferase (encoded by the FUT1 gene, also called the H gene).

Here is the critical concept: The A and B genes encode glycosyltransferases that add additional sugars to the H antigen.

- The A gene encodes an N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase that adds N-acetylgalactosamine to the H antigen, creating the A antigen

- The B gene encodes a galactosyltransferase that adds galactose to the H antigen, creating the B antigen

- The O gene is a null allele (due to a frameshift mutation) that produces no functional enzyme, so the H antigen remains unmodified

This means: - Type A individuals have A antigens (modified H) on their cells - Type B individuals have B antigens (modified H) on their cells - Type AB individuals have both A and B antigens - Type O individuals have only unmodified H antigen

The Bombay Phenotype: When the Foundation Is Missing

The Bombay phenotype (Oh) occurs when an individual lacks functional FUT1 gene and therefore cannot make the H antigen. Without the H antigen foundation, neither A nor B antigens can be synthesized, regardless of what ABO genes the person has inherited.

Bombay individuals have: - No A, B, or H antigens on their red cells - Anti-A, anti-B, AND anti-H antibodies in their plasma

This creates a dangerous situation: Bombay individuals can only receive blood from other Bombay donors. If given type O blood (which has abundant H antigen), they will have a severe hemolytic reaction due to their anti-H antibodies.

ABO Subgroups: When A Isn’t Just A

Not all type A individuals are created equal. The A1 and A2 subgroups represent quantitative and qualitative differences in A antigen expression:

A1 (approximately 80% of type A individuals): - Express more A antigen on their red cells - Express both A and A1 antigens (A1 is a branched form) - Strong reactions with anti-A reagents

A2 (approximately 20% of type A individuals): - Express less A antigen (approximately 25% as much) - Do not express the A1 antigen - May develop anti-A1 antibodies (found in about 1-8% of A2 individuals and 25% of A2B individuals)

The clinical significance: A2 individuals with anti-A1 can usually receive A1 blood without problems because anti-A1 is typically IgM and reacts only at cold temperatures. However, in rare cases where anti-A1 is reactive at 37°C, it can cause hemolysis.

ABO Discrepancies: When Forward and Reverse Don’t Match

In ABO typing, we perform two complementary tests: - Forward typing: Testing the patient’s red cells with known anti-A and anti-B reagents - Reverse typing: Testing the patient’s plasma with known A1 and B red cells

These should agree. When they don’t, you have an ABO discrepancy that must be resolved before transfusion.

Common causes of discrepancies include:

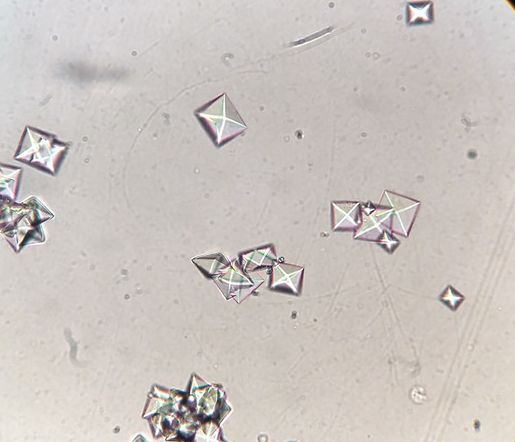

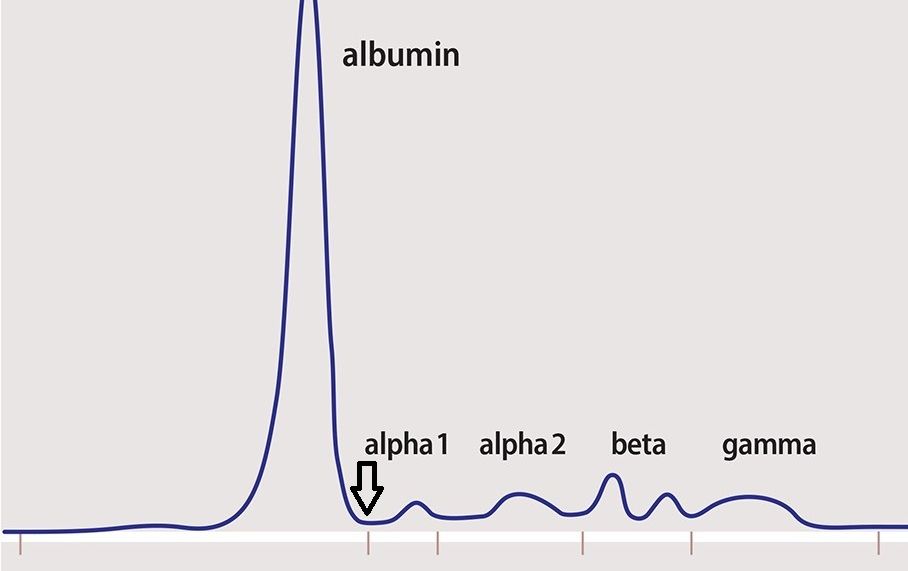

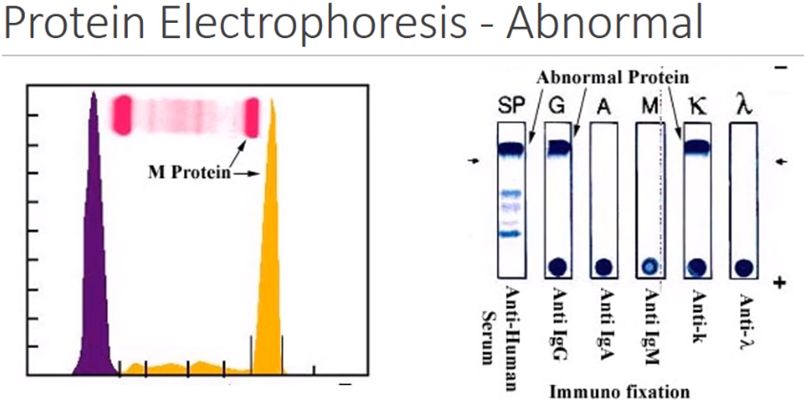

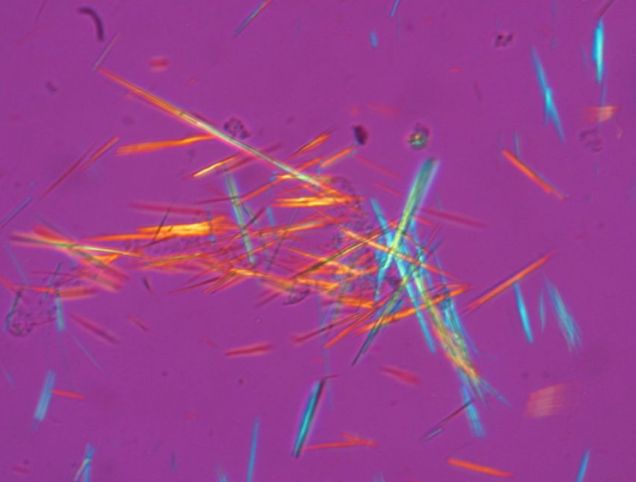

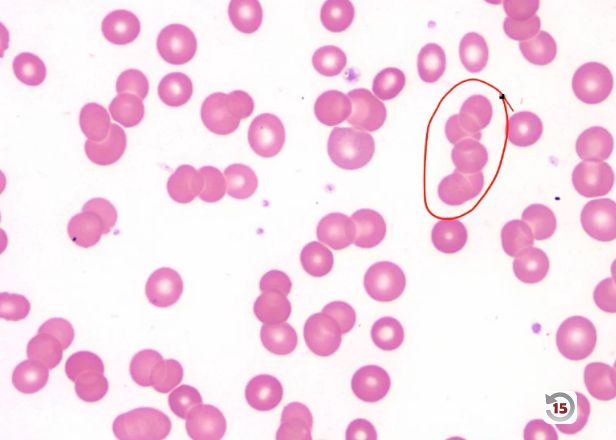

Extra reactions in forward typing (cells appear to type as more than one blood type): - Polyagglutination (T-activation from bacterial neuraminidase exposure) - Autoantibodies coating red cells - Recently transfused with non-identical ABO type - Rouleaux (protein coating causing stacking-seen in multiple myeloma, hyperglobulinemia)

Weak or missing reactions in forward typing: - ABO subgroups (A2, A3, Ax, etc.) - Disease states reducing antigen expression - Heavily transfused patients - Bone marrow transplant recipients (mixed field reactions during engraftment)

Extra reactions in reverse typing: - Cold autoantibodies (often anti-I) - Cold alloantibodies - Rouleaux - High-titer, low-avidity (HTLA) antibodies

Weak or missing reactions in reverse typing: - Age extremes (infants don’t make isohemagglutinins until ~4-6 months; elderly may have diminished production) - Immunocompromised patients (hypogammaglobulinemia) - Recent plasma transfusion or plasma exchange

1.3 The Rh Blood Group System: Complexity Beyond D

The Rh system is the second most important blood group system clinically and the most complex genetically, with over 50 different antigens. However, for practical purposes, five antigens matter most: D, C, c, E, and e.

Understanding Rh Genetics

The Rh antigens are encoded by two closely linked genes on chromosome 1: - RHD encodes the D antigen - RHCE encodes the C/c and E/e antigens

The D antigen is either present (Rh-positive, ~85% of Caucasians) or absent (Rh-negative, ~15% of Caucasians). There is no “d” antigen-lowercase d simply indicates the absence of D.

The C/c and E/e antigens are antithetical pairs: - C and c differ by four amino acids in the second extracellular loop of the RhCE protein - E and e differ by a single amino acid (proline vs. alanine) at position 226

Most people express both members of each antithetical pair because they inherit different RHCE alleles from each parent. For example, someone who is Ce/cE expresses all four antigens: C, c, E, and e.

The D Antigen: Why It Matters So Much

The D antigen is highly immunogenic-meaning it very effectively stimulates antibody production. Approximately 80% of D-negative individuals who receive a single D-positive red cell transfusion will develop anti-D. This makes D the most immunogenic blood group antigen after A and B.

Anti-D is: - Almost always IgG (not IgM) - Clinically significant-causes both acute and delayed hemolytic reactions - The most common cause of severe hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN)

Because of its clinical importance, we classify everyone as Rh-positive or Rh-negative based solely on D status, and we give RhIG (Rh immune globulin) to D-negative pregnant women to prevent sensitization.

Weak D: When D Testing Gets Complicated

Some individuals have red cells that react weakly or not at all with anti-D reagents during immediate-spin testing but react when the test is carried through the indirect antiglobulin test (IAT) phase. This is called weak D.

Weak D occurs due to: 1. Quantitative reduction in D antigen expression (fewer D antigens on each cell) 2. Caused by various RHD gene mutations that reduce but don’t eliminate D expression

The clinical significance: - Weak D individuals are generally considered D-positive for transfusion purposes (they can receive D-positive blood) - As donors, their blood is labeled D-positive - In pregnancy, weak D mothers were traditionally given RhIG to be safe, but current guidelines based on RHD genotyping may allow withholding RhIG for certain weak D types

Partial D: When D Is Missing Pieces

Partial D is fundamentally different from weak D. Partial D individuals: - Have altered D antigens missing certain epitopes (portions of the D antigen) - May make anti-D against the epitopes they lack - Can experience hemolytic reactions if transfused with D-positive blood

There are over 100 partial D types described, but some common ones include: - DVI: The most clinically significant; these individuals often make anti-D and should be considered D-negative for transfusion - DIIIa, DAR: Common in African Americans; less likely to make anti-D

The problem: Serologically, partial D often looks like weak D. Distinguishing them requires molecular (DNA) testing. Modern practice is moving toward RHD genotyping, especially in pregnant women, to make appropriate decisions about RhIG administration.

Rh Immunogenicity: The Hierarchy

Not all Rh antigens are equally immunogenic. The order from most to least immunogenic is: D > c > E > C > e

This matters clinically: - Anti-c is the second most common Rh antibody (after anti-D) and is a significant cause of HDFN - Anti-E is relatively common and usually clinically significant - Anti-C and anti-e are less common because most C-negative or e-negative individuals also lack D, and anti-D formation often overshadows these

1.4 The Kell Blood Group System: High Immunogenicity

The Kell system contains over 35 antigens, but the most important are K (Kell, K1) and k (cellano, K2).

Why Kell Matters

K is the third most immunogenic red cell antigen (after D and c). About 9% of Caucasians are K-positive; the rest are K-negative. Because K is highly immunogenic but relatively rare: - K-negative recipients are commonly exposed to K-positive blood - Anti-K formation is common after sensitization - Anti-K causes severe HDFN (and uniquely, suppresses erythropoiesis rather than just causing hemolysis)

The McLeod Phenotype: Kell and Beyond

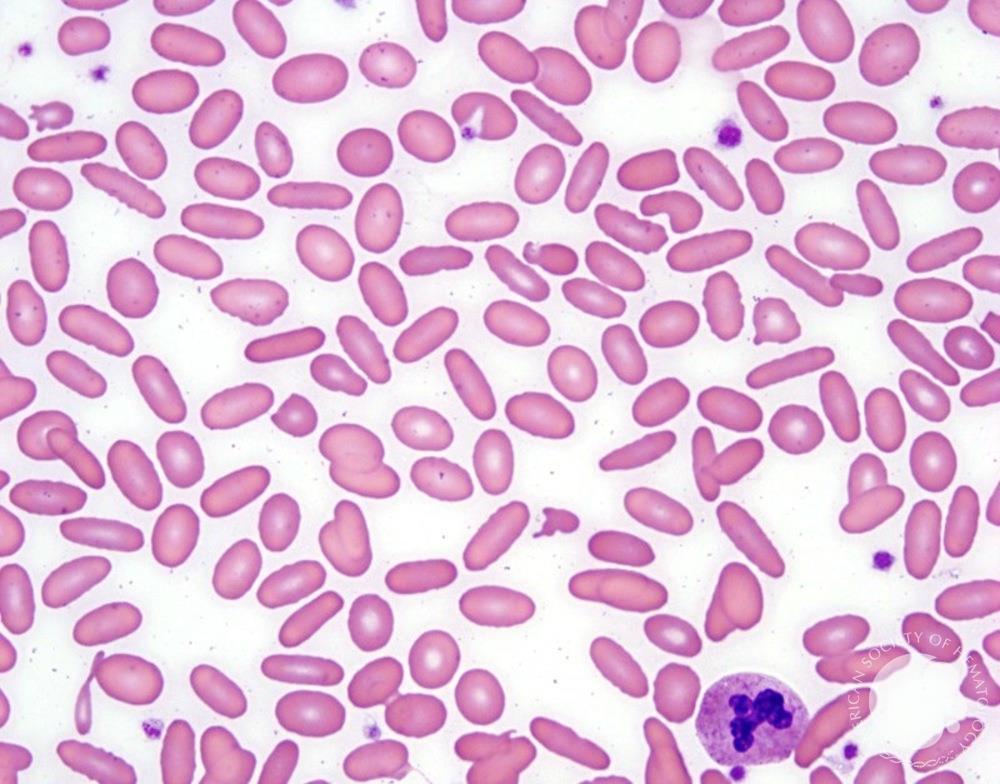

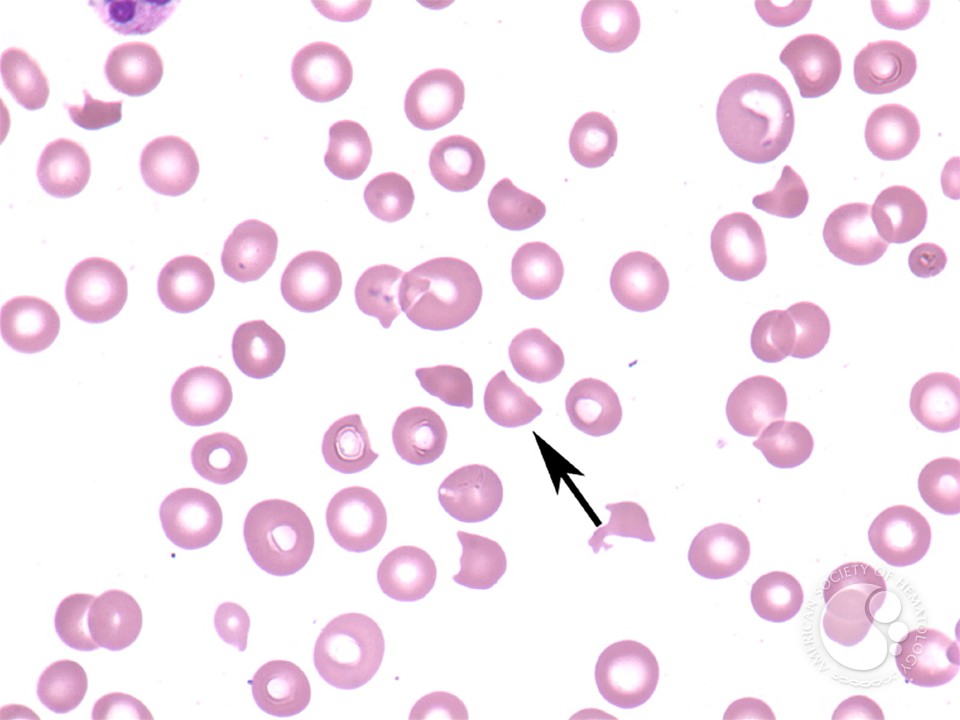

The Kell glycoprotein is linked to the XK protein, which carries the Kx antigen and is encoded on the X chromosome. McLeod syndrome occurs when the XK gene is deleted or mutated, resulting in: - Absent Kx antigen - Markedly reduced Kell antigen expression - Acanthocytes (spiky red cells) on peripheral smear - Late-onset neurological disease (resembling chorea) - Hemolytic anemia

McLeod individuals can only receive blood from other McLeod donors-their anti-Ku + anti-Km antibodies react with all Kell-system antigens.

1.5 The Duffy Blood Group System: Malaria Resistance

The Duffy system has two principal antigens: Fy(a) and Fy(b), encoded by alleles of the ACKR1 gene (formerly DARC-Duffy Antigen Receptor for Chemokines).

The Duffy-Malaria Connection

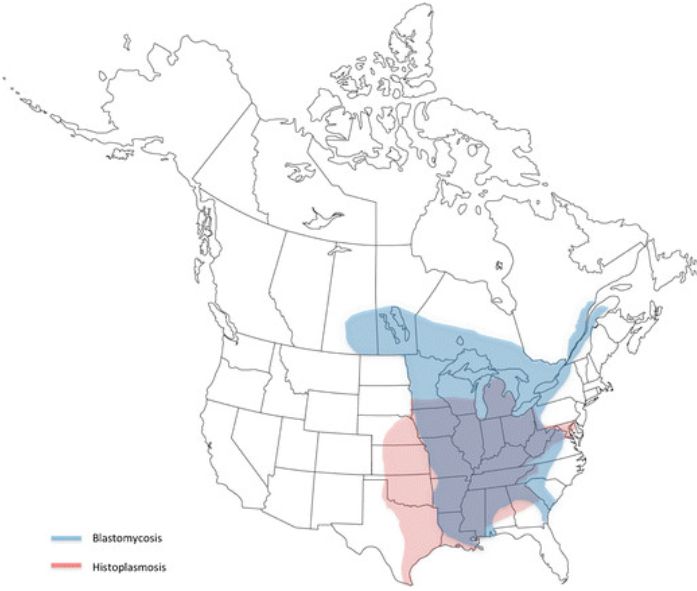

The Duffy glycoprotein serves as a receptor for chemokines-but it was evolutionarily co-opted by Plasmodium vivax as its entry point into red blood cells. This creates a fascinating example of natural selection:

In West Africa, where P. vivax malaria was historically endemic, a promoter mutation arose that prevents Duffy expression on red cells (while maintaining expression elsewhere). Individuals with this Fy(a-b-) phenotype are: - Completely resistant to P. vivax infection - Found in up to 70% of West African populations and their descendants

This is why P. vivax malaria is rare in sub-Saharan Africa-most of the population lacks the receptor the parasite needs.

Clinical Significance of Duffy Antibodies

Anti-Fya and anti-Fyb are clinically significant antibodies: - Usually IgG, reactive at 37°C - Can cause both acute and delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions - Can cause HDFN (usually mild to moderate)

Important laboratory concept: Duffy antigens are destroyed by ficin and papain (proteolytic enzymes used in antibody identification). If an antibody reacts in the standard panel but not after enzyme treatment, and shows the Duffy pattern, it’s likely anti-Fya or anti-Fyb.

1.6 The Kidd Blood Group System: The Notorious Cause of Delayed Reactions

The Kidd system has two principal antigens: Jk(a) and Jk(b), encoded by the SLC14A1 gene (a urea transporter).

Why Kidd Antibodies Are Dangerous

Kidd antibodies are notorious in blood banking for several reasons:

They cause delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions (DHTR): The classic scenario is a patient transfused without problems, then 3-14 days later develops anemia, jaundice, and a positive DAT. Investigation reveals a new Kidd antibody.

They disappear and reappear: Anti-Jka and anti-Jkb often fall below detectable levels, only to rapidly reappear (anamnestic response) upon re-exposure to antigen-positive cells.

They show dosage: Kidd antibodies react more strongly with cells from homozygotes (Jk(a+b-) or Jk(a-b+)) than heterozygotes (Jk(a+b+)). This can cause weak or negative antibody screens if screening cells are heterozygous.

They fix complement: Kidd antibodies efficiently activate complement, which explains why DHTR from anti-Kidd often has an intravascular hemolysis component.

The clinical lesson: Always consider Kidd antibodies in patients with delayed hemolytic reactions, even if the antibody screen is negative. Historical records are crucial-if a patient had anti-Jka five years ago, assume they still have it and provide Jk(a-) blood.

1.7 Other Blood Group Systems: What You Need to Know

The MNS System

The MNS system antigens are carried on glycophorins A (M and N antigens) and B (S and s antigens). Key points:

- Anti-M: Usually naturally occurring IgM, cold-reactive, clinically insignificant. May rarely be IgG and cause HDFN.

- Anti-N: Rare and almost never clinically significant

- Anti-S and anti-s: IgG, clinically significant, can cause hemolytic reactions and HDFN

- MNS antigens are destroyed by enzymes (ficin, papain)-useful in antibody identification

The Lewis System

Lewis antigens (Le(a) and Le(b)) are unique because: - They are not synthesized by the red cell-they’re made in secretory tissue and adsorbed onto the red cell membrane from plasma - They’re not present at birth; they develop over the first two years of life - Expression depends on Lewis and Secretor gene inheritance

Lewis phenotypes and genetics: - Le(a+b-): Has Lewis gene, lacks Secretor gene - Le(a-b+): Has both Lewis and Secretor genes (Secretor converts Le(a) to Le(b)) - Le(a-b-): Lacks Lewis gene (common in Black individuals, ~30%)

Clinical significance: Anti-Lea and anti-Leb are almost always IgM, reactive only at cold temperatures, and clinically insignificant. They do not cause HDFN (IgM doesn’t cross the placenta) and rarely cause hemolytic reactions. Most blood banks consider them nuisance antibodies.

The I/i System

I and i antigens are not antithetical-they represent developmental differences in carbohydrate chain branching: - i antigen: Linear chains, predominant on fetal/cord blood cells - I antigen: Branched chains, predominant on adult cells

Anti-I is a common cold autoantibody: - Found in cold agglutinin disease (often following Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection) - IgM, reactive at cold temperatures - Clinically significant when thermal amplitude extends near 37°C

Anti-i is rare but associated with infectious mononucleosis (EBV infection).

The P1PK System

The P1 antigen is highly variable in expression. Anti-P1 is: - Usually naturally occurring IgM - Clinically insignificant (cold-reactive) - Common (found in ~30% of P1-negative individuals)

The very rare anti-PP1Pk (formerly anti-Tja) reacts with cells from 99.9% of people and is associated with early spontaneous abortions.

Chapter 2: Antibody Identification and Compatibility Testing

2.1 The Antiglobulin Test: The Foundation of Modern Blood Banking

The antiglobulin test (Coombs test) is perhaps the single most important tool in transfusion medicine. Understanding it deeply is essential.

The Principle

Human antibodies (IgG) and complement fragments (C3d) bound to red blood cells are invisible to the naked eye-they don’t directly cause agglutination. The antiglobulin test makes them visible:

Anti-human globulin (AHG) is an antibody (made in animals) directed against human IgG and/or human complement components. When AHG is added to red cells coated with IgG or C3d, it cross-links the antibodies/complement, creating visible agglutination.

Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT)

The DAT detects antibodies or complement already bound to the patient’s red cells in vivo. The procedure: 1. Wash the patient’s red cells (to remove unbound proteins) 2. Add polyspecific AHG (contains both anti-IgG and anti-C3d) 3. If positive, test with monospecific AHG to determine what’s on the cells

Clinical interpretation of DAT results:

| DAT Result | IgG | C3d | Possible Causes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | + | - | Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia, drug-induced (methyldopa type), HDFN, alloantibody-coated cells |

| Positive | - | + | Cold agglutinin disease (IgM elutes during washing, leaves complement), some drug-induced |

| Positive | + | + | Warm AIHA, drug-induced (immune complex), some alloantibodies |

| Negative | - | - | Normal; IgM-only sensitization; low-level sensitization below test threshold |

Important nuances: - A positive DAT doesn’t always mean hemolysis is occurring-many hospitalized patients have positive DATs without hemolysis - A negative DAT doesn’t rule out immune hemolysis-some antibodies are low-affinity and wash off - Drug-induced antibodies may require special techniques (including the drug) to detect

Indirect Antiglobulin Test (IAT)

The IAT detects antibodies in the patient’s serum/plasma that bind to reagent red cells in vitro. The procedure: 1. Incubate patient serum with reagent red cells at 37°C 2. Wash cells (to remove unbound proteins) 3. Add AHG 4. Read for agglutination

The IAT is used in: - Antibody screening - Antibody identification - Crossmatching - Phenotyping with certain reagents

2.2 Antibody Screening: The First Line of Defense

Before transfusion, every patient receives an antibody screen to detect clinically significant unexpected antibodies.

The Method

The antibody screen tests patient plasma against 2-3 reagent screening cells with known antigen profiles. These cells are group O (to avoid ABO reactions) and are selected to express all common clinically significant antigens between them.

The screen is performed using IAT methodology: - Incubation at 37°C (to detect clinically significant IgG antibodies) - Addition of AHG - Reading for agglutination

Enhancement Media

To increase sensitivity, most modern screens use enhancement reagents:

LISS (Low Ionic Strength Saline): Reduces the ionic cloud around red cells, bringing antibody and antigen closer together. Increases antibody uptake, reduces incubation time.

PEG (Polyethylene Glycol): Concentrates antibodies by excluding water, forcing antibody-antigen interactions. Highly sensitive but can cause false positives; must wash before adding AHG.

Gel or solid-phase technology: Modern platforms that capture antibody-antigen reactions in a gel column or on a solid surface. More standardized and amenable to automation.

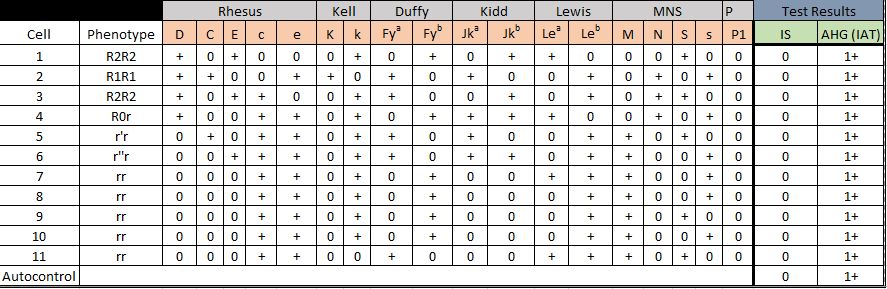

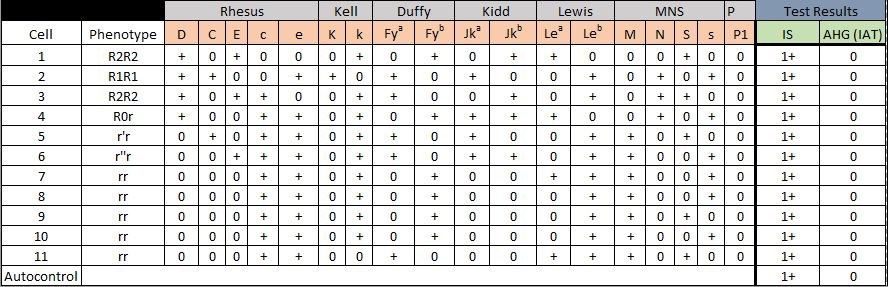

2.3 Antibody Identification: The Art of Pattern Recognition

When the antibody screen is positive, you must identify the antibody. This is both a science and an art.

The Panel

An antibody identification panel consists of 10-16 group O reagent cells with known antigen profiles. You test the patient’s plasma against each cell and record reactivity.

The Rule-Out Process

For each antigen on the panel, you can potentially “rule out” the corresponding antibody if: - At least one cell that is positive for the antigen is non-reactive with the patient’s plasma

For example, if cell #3 is K+ (Kell positive) and the patient’s plasma does not react with cell #3, you can rule out anti-K.

The standard of practice is the “rule of three”-for statistical confidence, you need: - At least 3 antigen-positive cells reacting with the plasma - At least 3 antigen-negative cells NOT reacting with the plasma

This gives statistical significance (p < 0.05) that the association is real.

Reading the Pattern

After running the panel, you look at which cells react and don’t react. You then correlate this with the antigen profile: - Which antigens are present on all reacting cells? - Which antigens are absent on non-reacting cells?

The antibody specificity should explain the reactivity pattern.

Complications in Antibody Identification

Real-world cases are often more complex:

Multiple antibodies: The patient has more than one antibody. The pattern won’t fit a single specificity. Solutions: - Selected cell panels with cells positive for one suspected antigen and negative for another - Antibody removal techniques (adsorption) to separate and identify each antibody

Dosage effect: Some antibodies (Kidd, Duffy, MNS, Rh c/C/e/E) react more strongly with cells from homozygotes. If your panel is mostly heterozygotes, you might see weak or variable reactions.

Cold antibodies interfering: Cold-reactive IgM antibodies (anti-I, anti-M, anti-Lewis) can cause positive reactions at room temperature, confusing the pattern. Solutions: - Test strictly at 37°C - Pre-warm technique - Enzyme treatment (destroys some cold-reactive antigens)

Autoantibody: If the DAT is positive and the patient appears to have a pan-reactive pattern, they may have an autoantibody. Autoantibodies coat the patient’s own cells and react with all panel cells.

Special Techniques

Enzyme treatment: Treating cells with ficin or papain: - Destroys: Duffy, MNS antigens - Enhances: Rh, Kidd, Lewis - Useful for: Unmasking Rh or Kidd antibodies behind Duffy antibodies, evaluating cold-reactive antibodies

DTT (Dithiothreitol): Denatures IgM antibodies; useful for: - Eliminating IgM cold antibodies to see underlying IgG - Note: Also destroys Kell antigens

Adsorption: Removing antibodies from serum by incubating with antigen-positive cells: - Autoadsorption: Patient’s own cells remove autoantibody, leaving alloantibodies - Differential adsorption: Selected cells remove specific alloantibodies

Elution: Recovering antibodies from the red cell surface for identification. Methods include acid elution, heat elution, and freeze-thaw elution.

2.4 Compatibility Testing: Putting It All Together

The Type and Screen

For most patients, a “type and screen” is sufficient before surgery: - ABO/Rh typing - Antibody screen

If the screen is negative and the patient has no history of antibodies, blood can be rapidly provided with an abbreviated crossmatch.

The Crossmatch

The crossmatch tests compatibility between the specific donor unit and the patient:

Immediate-spin crossmatch: Just ABO compatibility check. Appropriate only when: - Current antibody screen is negative - No history of clinically significant antibodies

Full (antiglobulin) crossmatch: Includes 37°C incubation and AHG phase. Required when: - Current antibody screen is positive - Patient has a history of clinically significant antibodies

Electronic crossmatch: Computer verification that ABO-compatible blood is selected. Requirements: - Two separate ABO/Rh typings on file (from different samples) - Current negative antibody screen - Validated computer system

The electronic crossmatch is now standard at many institutions-it’s fast and eliminates the serological crossmatch when appropriate.

Urgent Transfusion: When There’s No Time

In emergencies, uncrossmatched blood may be necessary:

O-negative red cells: The “universal donor” for red cells-no A, B, or D antigens to cause immediate hemolysis. Use for: - Unknown blood type - D-negative women of childbearing potential

O-positive red cells: Acceptable for males and post-menopausal females when O-negative is scarce

Type-specific, uncrossmatched: Once ABO/Rh is known (takes ~5 minutes), switch to type-specific blood

AB plasma: The “universal donor” for plasma-no anti-A or anti-B to cause hemolysis

Document the clinical urgency when releasing uncrossmatched blood.

Blood Product Compatibility Quick Reference

Red Blood Cell Compatibility (based on recipient’s ABO type):

| Patient Blood Type | Can Receive RBCs From |

|---|---|

| O | O only |

| A | A, O |

| B | B, O |

| AB | A, B, AB, O (universal recipient) |

Rh Consideration: Rh-negative patients should receive Rh-negative RBCs. Rh-positive patients can receive either. In emergencies, Rh-positive blood can be given to Rh-negative males and post-menopausal females when Rh-negative is unavailable.

Plasma Compatibility (opposite of RBCs-based on what antibodies the plasma contains):

| Patient Blood Type | Can Receive Plasma From |

|---|---|

| O | O, A, B, AB |

| A | A, AB |

| B | B, AB |

| AB | AB only |

Key Principle: For RBCs, you avoid giving antigens the patient has antibodies against. For plasma, you avoid giving antibodies that will attack the patient’s RBCs. This is why O is the universal RBC donor but AB is the universal plasma donor.

Chapter 3: Blood Components and Their Clinical Use

3.1 Component Preparation and Anticoagulant-Preservative Solutions

Understanding how blood components are prepared and stored is essential for understanding their clinical properties.

Whole Blood Processing

Whole blood collection yields approximately 450-500 mL of blood mixed with 63-70 mL of anticoagulant-preservative solution. From this single donation, multiple components can be prepared:

Centrifugation steps: 1. Soft spin (2000g × 3 minutes): Separates packed RBCs from platelet-rich plasma (PRP) 2. Hard spin (5000g × 5 minutes): Separates platelets from plasma 3. Cryoprecipitate preparation: Slow thawing of FFP at 1-6°C causes cold-insoluble proteins to precipitate; a second hard spin separates cryoprecipitate from cryo-poor plasma

The density hierarchy (from least to most dense): Plasma < Platelets < Lymphocytes < Monocytes < Neutrophils < Red cells. This is why centrifugation effectively separates components.

Anticoagulant-Preservative Solutions

Traditional solutions (used alone):

| Solution | Key Features | RBC Shelf Life |

|---|---|---|

| CPD | Citrate + Phosphate + Dextrose | 21 days |

| CP2D | Double dextrose compared to CPD | 21 days |

| CPDA-1 | CPD + Adenine | 35 days |

The role of each component: - Citrate: Anticoagulant-chelates calcium to prevent clotting - Phosphate: Buffer-maintains pH to support glycolysis - Dextrose: Fuel-metabolized via glycolysis to generate ATP - Adenine: ATP precursor-directly supports ATP synthesis, extending RBC viability

Additive solutions (AS-1, AS-3, AS-5, AS-7): - Added to RBCs after plasma removal - Extend shelf life to 42 days - Allow more plasma to be harvested (better platelet and FFP yield) - Result in lower hematocrit (~55-65%) making transfusion easier

| Additive Solution | Brand Name | Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| AS-1 | Adsol | Dextrose, adenine, mannitol, NaCl |

| AS-3 | Nutricel | Dextrose, adenine, phosphate, citrate, NaCl |

| AS-5 | Optisol | Similar to AS-1, less mannitol |

| AS-7 | SOLX | Newer formulation with improved RBC recovery |

Mannitol in AS-1 and AS-5 serves as a membrane stabilizer, reducing hemolysis during storage.

Quality Control Standards for Blood Components

| Component | Quality Control Requirement |

|---|---|

| RBCs (additive solution) | Hct ≤80%; ≥75% recovery at 24 hours post-transfusion |

| Leukoreduced RBCs | <5 × 10^6 WBCs; retain ≥85% original RBCs |

| Apheresis platelets | ≥3 × 10^11 platelets; pH ≥6.2 at outdate |

| Whole blood platelets | ≥5.5 × 10^10 platelets per unit; pH ≥6.2 |

| FFP | All clotting factors ≥1 IU/mL |

| Cryoprecipitate | ≥80 IU Factor VIII; ≥150 mg fibrinogen per unit |

| Irradiated products | 25 Gy to center; ≥15 Gy at all points |

3.2 Red Blood Cell Products

The Storage Lesion

During storage, red cells undergo progressive changes-the “storage lesion”:

- Decreased 2,3-DPG: Shifts the oxygen dissociation curve left, reducing oxygen delivery. Levels recover within 12-24 hours post-transfusion.

- Decreased ATP: Compromises membrane integrity

- Increased potassium: RBCs leak K+ as the Na-K-ATPase fails. Fresh units have ~4 mEq/L supernatant K+; 42-day units may have 40-50 mEq/L

- Decreased pH: Lactate accumulates from anaerobic glycolysis

- Microvesicle formation: Membrane blebs form

- Increased free hemoglobin: Cellular lysis releases hemoglobin

Clinical relevance: - Neonates and massive transfusion patients may be affected by high K+ and low pH - Most changes are rapidly reversed after transfusion in stable patients - There’s ongoing debate about whether “fresh” blood improves outcomes; current evidence doesn’t support routine use of only fresh units

Modified RBC Products

Leukoreduced RBCs: Contains <5 × 10^6 white blood cells (>99.9% reduction)

How it’s made: Filtration through specialized filters during collection (prestorage) or before transfusion

Benefits: - Reduces febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions (caused by WBC cytokines and recipient anti-HLA antibodies) - Reduces HLA alloimmunization (important for patients who may need platelet transfusions or transplant) - Reduces CMV transmission (CMV lives in WBCs; leukoreduction is considered “CMV-safe”)

Currently, over 90% of RBCs in the US are universally leukoreduced.

Irradiated RBCs: Exposed to 25-50 Gy gamma radiation

Purpose: Prevents transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease (TA-GVHD)

How it works: Inactivates donor T-lymphocytes that could engraft and attack the recipient’s tissues

Indications: - Immunocompromised recipients (congenital immunodeficiency, hematologic malignancies, stem cell transplant) - HLA-matched or HLA-selected products - Directed donations from blood relatives - Intrauterine transfusions - Neonates (especially premature or those receiving exchange transfusion)

Side effect: Accelerates K+ leak (irradiation damages the RBC membrane). Irradiated units should ideally be used within 28 days or less.

Washed RBCs: RBCs washed with saline to remove plasma proteins

Indications: - IgA-deficient patients with anti-IgA (prevents anaphylaxis) - Severe allergic reactions not controlled by premedication - T-activated cells (washing removes plasma containing antibodies to T antigen)

Drawbacks: Time-consuming, shortens shelf life to 24 hours, results in some RBC loss

Frozen/Deglycerolized RBCs: Cryopreserved using glycerol, stored at -65°C (10-year shelf life)

Use: Storing rare blood types. After thawing and deglycerolization (washing out the glycerol), shelf life is 24 hours (open system) to 14 days (closed system).

3.3 Platelet Products

Platelet Biology Relevant to Storage

Platelets are far more delicate than red cells: - Must be stored at room temperature (20-24°C)-cold causes irreversible aggregation and shape change - Require continuous gentle agitation to allow gas exchange - Have short shelf life (5 days, extended to 7 days with pathogen reduction) - Are prone to bacterial contamination (room temperature storage allows bacterial growth)

Types of Platelet Products

Whole blood-derived platelets: Made by centrifuging whole blood donations - Platelet-rich plasma method: Soft spin to separate PRP, then hard spin to pellet platelets - Buffy coat method: Hard spin to separate buffy coat (WBCs and platelets), then light spin to separate platelets - One unit contains ~5.5 × 10^10 platelets - Usually pooled (4-6 units) to provide a therapeutic dose (~3 × 10^11 platelets)

Apheresis platelets: Collected by apheresis from a single donor - Contains ~3 × 10^11 platelets (equivalent to ~6 pooled whole blood units) - Single donor exposure - Lower bacterial contamination risk - Can be HLA-matched if needed

Platelet Transfusion Dosing

A standard adult dose (one apheresis unit or one pool) should raise the platelet count by: - Approximately 30,000-50,000/μL in a 70 kg adult - Or can be calculated as: Increment = (Platelets transfused × 0.67) / Blood volume (L)

Corrected Count Increment (CCI): Used to assess platelet transfusion response - CCI = (Post-transfusion count - Pre-transfusion count) × BSA (m²) / Platelets transfused (× 10^11) - Normal CCI at 1 hour: >7,500 - Normal CCI at 24 hours: >4,500 - Lower than expected suggests refractoriness

Platelet Refractoriness

When a patient has repeated poor platelet increments, they’re considered refractory. Causes are divided into:

Non-immune causes (more common, ~80%): - Splenomegaly (platelet sequestration) - Fever/sepsis (increased consumption) - DIC (consumption) - Medications (amphotericin B, vancomycin) - Bleeding (consumption)

Immune causes (~20%): - HLA antibodies (most common immune cause): Recipient has antibodies to donor HLA Class I antigens on platelets - HPA (Human Platelet Antigen) antibodies: Less common

Management: - For non-immune: Treat underlying cause; consider more frequent transfusions - For immune: - HLA-matched platelets (requires HLA typing and HLA-matched donor inventory) - Crossmatch-compatible platelets (test recipient serum against donor platelets) - Platelet serial ABO matching (sometimes helps)

3.4 Plasma Products

Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP)

FFP is plasma separated from whole blood and frozen within 8 hours of collection at ≤-18°C (or within 24 hours for “PF24”).

Contents: - All coagulation factors (including V and VIII) - Fibrinogen (~200-400 mg per unit) - Plasma proteins (albumin, immunoglobulins) - Volume ~200-250 mL per unit

Clinical uses: - Replacement of multiple coagulation factors (liver disease, DIC, massive transfusion) - Reversal of warfarin (when PCC not available or contraindicated) - TTP therapeutic plasma exchange (replacement fluid) - Rare factor deficiencies without specific concentrates

Dosing: 10-20 mL/kg (typically 4-6 units in an adult) to achieve 20-30% factor activity increase

Important concept: FFP must be ABO-compatible with the recipient’s red cells: - Type A recipients can receive A or AB plasma - Type B recipients can receive B or AB plasma - Type O recipients can receive O, A, B, or AB plasma - Type AB recipients can receive only AB plasma

AB plasma is the “universal donor” for plasma because it contains no anti-A or anti-B.

Thawed plasma: FFP thawed and stored at 1-6°C for up to 5 days. Has reduced levels of factors V and VIII but is suitable for most indications.

Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate is the cold-insoluble portion of plasma that precipitates when FFP is slowly thawed at 1-6°C.

Contents (per unit): - Fibrinogen: ≥150 mg (usually ~250 mg) - Factor VIII: ≥80 IU - Factor XIII - von Willebrand factor - Fibronectin

Volume: ~15 mL per unit (small volume is an advantage for fluid-restricted patients)

Indications: - Fibrinogen replacement (hypofibrinogenemia, DIC, massive transfusion) - Target fibrinogen usually >100-150 mg/dL - Uremic bleeding (controversial; contains vWF) - Factor XIII deficiency - Previously used for hemophilia A and vWD (now use specific concentrates)

Dosing for fibrinogen replacement: - One unit raises fibrinogen ~5-10 mg/dL in a 70 kg adult - Typical dose: 10 units (one “pool”) - Expected increase: ~50-100 mg/dL

Cryoprecipitate-reduced plasma (cryo-poor plasma): Plasma remaining after cryoprecipitate is removed. Used specifically for TTP therapeutic plasma exchange (lacks large vWF multimers that might exacerbate the condition).

3.5 Other Blood Products

Granulocytes

Granulocyte transfusions are used for: - Severe neutropenia with documented infection not responding to antibiotics - Neutrophil dysfunction syndromes

Collection: Apheresis with donor stimulation (G-CSF ± steroids) to increase yield

Storage: Room temperature without agitation; 24-hour shelf life

Special considerations: - Must be irradiated (viable lymphocytes present) - Must be ABO and Rh compatible - CMV-negative or leukoreduced not possible (you’re transfusing WBCs) - Usually given daily until infection resolves or neutrophil recovery

Clinical efficacy is debated; recent trials showed modest benefit in certain settings.

Chapter 4: Transfusion Reactions

Understanding transfusion reactions requires integrating immunology, pathophysiology, and clinical medicine. Every reaction has a mechanism, and understanding that mechanism guides recognition and management.

4.1 Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (AHTR)

The Mechanism

AHTR occurs when the recipient’s antibodies destroy transfused red cells. The most common scenario is ABO incompatibility from clerical error-a unit labeled for one patient given to another.

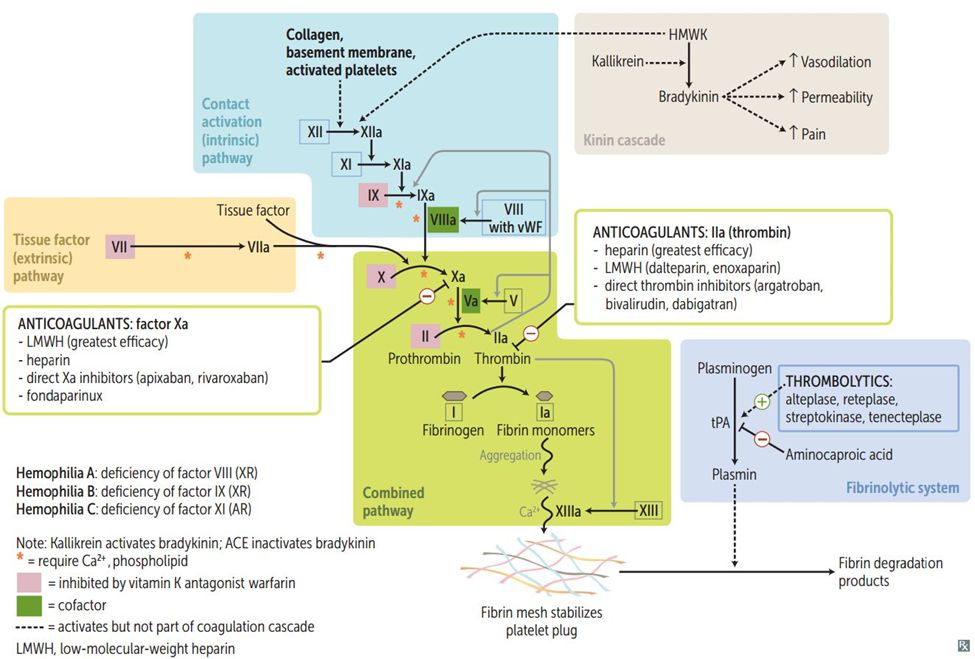

The pathophysiology: 1. Antibody binding: Pre-existing IgM antibodies (anti-A, anti-B) bind to incompatible donor red cells 2. Complement activation: IgM efficiently activates the classical complement pathway (C1 → C4 → C2 → C3 → C5-C9) 3. Membrane attack complex: C5-C9 creates pores in the red cell membrane, causing intravascular hemolysis 4. Cytokine storm: Complement fragments (C3a, C5a) and other mediators trigger massive inflammatory response 5. End-organ effects: - Hypotension from vasodilation - DIC from procoagulant release - Acute kidney injury from hemoglobin and cytokine effects on renal vasculature

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms can begin within minutes of starting transfusion: - Fever, chills (sometimes the only sign in anesthetized patients) - Chest pain, back pain, flank pain - Hypotension - Dark urine (hemoglobinuria) - Anxiety, sense of doom - Bleeding from DIC

In anesthetized patients: Hemoglobinuria, hypotension, and diffuse bleeding may be the only signs.

Laboratory Findings

- Positive DAT (often mixed-field due to mix of patient and donor cells)

- Hemoglobinemia (pink/red plasma)

- Hemoglobinuria (pink/red urine with positive blood on dipstick but no RBCs on microscopy)

- Decreased haptoglobin (bound by free hemoglobin)

- Elevated LDH (released from lysed cells)

- Elevated indirect bilirubin (delayed, from hemoglobin metabolism)

- Elevated creatinine (acute kidney injury)

- Coagulation abnormalities (prolonged PT/aPTT, low fibrinogen, elevated D-dimer) if DIC develops

Management

- Stop the transfusion immediately

- Maintain IV access with normal saline

- Support blood pressure (fluids, vasopressors if needed)

- Maintain urine output >1 mL/kg/hr (fluids, diuretics if needed; goal is to prevent renal tubular damage from hemoglobin)

- Clerical check: Verify patient identification and unit labeling

- Send blood bank samples: Post-transfusion patient sample, the unit with attached segment, and tubing

- Monitor and treat DIC if it develops

- Anticipate and treat acute kidney injury

4.2 Delayed Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (DHTR)

The Mechanism

DHTR occurs when a patient who was previously sensitized to a red cell antigen receives antigen-positive blood. At the time of transfusion, the antibody has waned below detectable levels. Exposure to the antigen triggers an anamnestic (memory) response:

- Memory B cells recognize the antigen

- Rapid proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells

- IgG antibody production within days

- Antibody-coated donor cells are removed primarily by the spleen (extravascular hemolysis)

Timing: 3-14 days post-transfusion (typically 5-7 days)

Common antibodies causing DHTR: - Kidd (especially Jka): The classic culprit; notorious for falling below detectable levels - Duffy (Fya) - Kell - Rh (C, c, E, e)

Clinical Presentation

Often subtle: - Falling hemoglobin or failure to achieve expected post-transfusion hemoglobin - Low-grade fever - Mild jaundice - Symptoms may be mistaken for other conditions (sepsis, bleeding)

Some patients have an intravascular component and present more dramatically (especially with Kidd antibodies).

Laboratory Findings

- Positive DAT (usually IgG; may be mixed-field)

- New alloantibody detected on antibody screen (wasn’t present before transfusion)

- Evidence of hemolysis: Elevated LDH, elevated indirect bilirubin, decreased haptoglobin

- Reticulocytosis (compensatory response)

Management

- Usually supportive; most cases are self-limited

- Transfuse if needed with antigen-negative blood

- Ensure the new antibody is documented for future transfusions

The key lesson: Maintain historical antibody records. A patient who made anti-Jka once should receive Jk(a-) blood forever, even if the current screen is negative.

4.3 Febrile Non-Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction (FNHTR)

The Mechanism

Two mechanisms contribute:

- Recipient antibodies to donor WBCs/HLA: The recipient’s anti-HLA antibodies react with donor leukocytes, causing cytokine release

- Cytokines accumulated during storage: Donor WBCs release IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α during storage; these are transfused and cause fever

The relative contribution depends on whether the product is leukoreduced: - Non-leukoreduced: Both mechanisms contribute - Prestorage leukoreduced: Mainly the second mechanism (fewer WBCs to make cytokines) - Leukoreduction has significantly reduced FNHTR incidence

Clinical Presentation

- Temperature rise ≥1°C (or 2°F) during or within 4 hours of transfusion

- Chills and rigors

- No hemolysis (this is the key distinguishing feature)

Differential Diagnosis

The challenge: Fever during transfusion could be: - FNHTR (benign) - AHTR (life-threatening) - Septic transfusion reaction (life-threatening) - Unrelated fever (patient’s underlying condition)

You must always consider AHTR and sepsis before diagnosing FNHTR.

Management

- Stop or slow the transfusion

- Evaluate for hemolysis (clerical check, visual inspection of plasma, DAT)

- Consider sepsis workup if clinically indicated

- Antipyretics for symptom relief

- If FNHTR is confirmed and patient needs more blood: Premedicate with acetaminophen; ensure products are leukoreduced

4.4 Allergic Reactions

Allergic reactions to transfusion range from mild urticaria to life-threatening anaphylaxis.

Mild Allergic Reactions (Urticaria)

Mechanism: IgE-mediated reaction to plasma proteins

Presentation: - Urticaria (hives) - Pruritus - No respiratory or cardiovascular compromise

Management: - May slow or stop transfusion - Antihistamines (diphenhydramine) - If symptoms resolve after antihistamine, may cautiously resume transfusion - For patients with recurrent urticarial reactions: Premedicate with antihistamines

Anaphylactic Reactions

Mechanism: Multiple possible causes: - IgA deficiency with anti-IgA: The classic teaching. Patients who completely lack IgA can make antibodies (IgG or IgE class) against IgA. When transfused with IgA-containing products, severe anaphylaxis can occur. - Other plasma protein antibodies: Anti-haptoglobin, anti-C4, etc. - IgE to other allergens in donor plasma

Presentation: - Rapid onset after starting transfusion (often within minutes) - Hypotension, bronchospasm, stridor - May have urticaria and angioedema - Can be fatal

Management: - Stop transfusion immediately - Epinephrine (first-line for anaphylaxis) - Maintain airway (intubation if needed) - IV fluids for hypotension - Antihistamines, steroids as adjuncts - Workup: Check IgA level and anti-IgA

Prevention for confirmed IgA deficiency with anti-IgA: - Washed cellular products (removes plasma) - Plasma products from IgA-deficient donors (rare; maintained in special registries)

4.6 Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO)

The Mechanism

TACO is straightforward: giving more volume than the cardiovascular system can handle. It’s cardiogenic pulmonary edema from transfusion.

Risk factors: - Advanced age - Pre-existing cardiac dysfunction - Renal failure - Small body size - Rapid transfusion rate - Large volume transfused

TACO is increasingly recognized as possibly the most common serious transfusion reaction, especially in elderly hospitalized patients.

Clinical Presentation

- Onset during or within 6 hours of transfusion

- Dyspnea, orthopnea

- Bilateral pulmonary edema

- Elevated blood pressure (unlike TRALI)

- Elevated jugular venous pressure

- Elevated BNP (typically >3 times baseline or >500 pg/mL)

Management

- Stop or slow transfusion

- Upright positioning

- Supplemental oxygen

- Diuretics (furosemide)

Prevention

- Transfuse slowly (1-2 mL/kg/hr for at-risk patients)

- Consider one unit at a time with reassessment

- Diuretic between units if needed

- Avoid unnecessary transfusions

4.7 Transfusion-Associated Graft-versus-Host Disease (TA-GVHD)

The Mechanism

TA-GVHD occurs when viable donor T-lymphocytes in a blood product engraft in the recipient and mount an immune attack against the recipient’s tissues.

Normally, the recipient’s immune system would recognize and destroy donor lymphocytes. TA-GVHD occurs when: - The recipient is severely immunocompromised (can’t reject donor cells), OR - The donor is homozygous for an HLA haplotype that the recipient is heterozygous for (recipient immune system sees donor cells as “self”)

The second scenario is why directed donations from blood relatives are risky: a parent or child often shares an HLA haplotype.

Clinical Presentation

Onset: 4-30 days post-transfusion (typically 8-10 days)

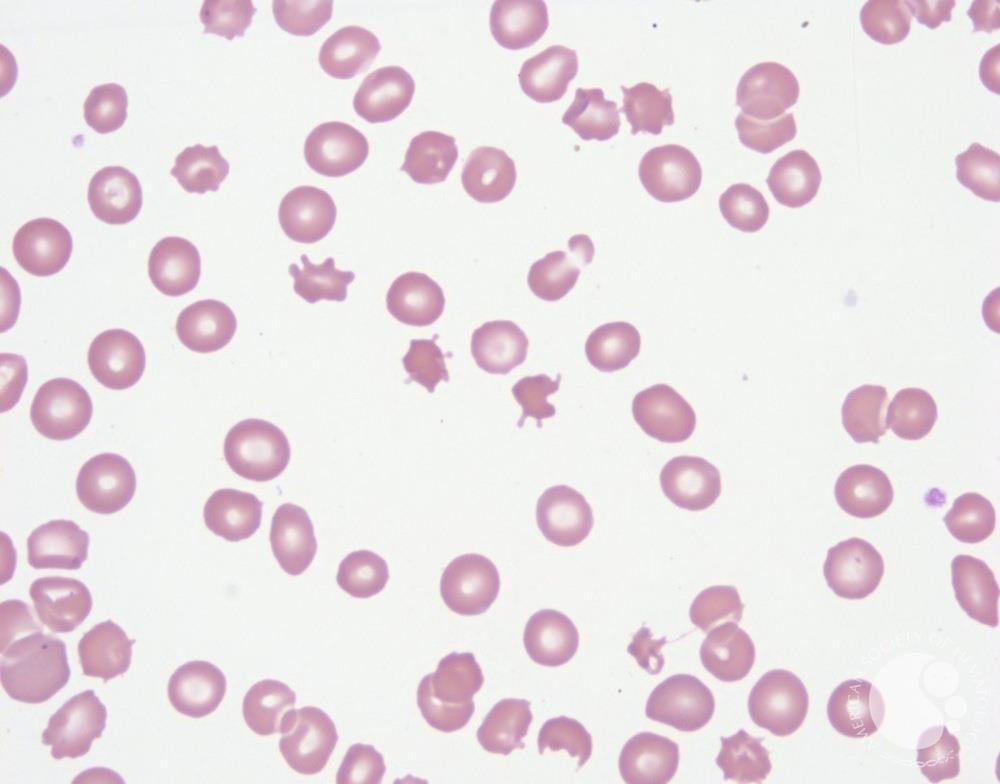

Classic features: - Rash (erythematous, often starting on face and trunk, can progress to desquamation) - Hepatitis (elevated transaminases, hyperbilirubinemia) - Diarrhea (watery, may be bloody) - Bone marrow aplasia: This is what makes TA-GVHD different from transplant GVHD and what makes it almost uniformly fatal

The bone marrow aplasia occurs because the donor T-cells attack the recipient’s hematopoietic stem cells (which, unlike in transplant GVHD, are recipient-origin and thus targets).

Prognosis

Mortality: >90%. Most patients die from infection secondary to pancytopenia.

There is no effective treatment. Prevention is critical.

Prevention

Irradiation of cellular blood products inactivates T-lymphocytes (requires 25-50 Gy).

Indications for irradiation: - Intrauterine transfusions - Exchange transfusions in neonates - Premature infants - Congenital immunodeficiency syndromes - Hematologic malignancies (especially Hodgkin lymphoma) - Recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants (before engraftment and often long-term) - Patients receiving purine analogs (fludarabine, cladribine) or other immunosuppressive chemotherapy - HLA-matched or HLA-selected products - Directed donations from blood relatives - Patients receiving granulocyte transfusions

4.8 Septic Transfusion Reactions

The Mechanism

Bacterial contamination of blood products can cause severe sepsis when transfused.

Sources of contamination: - Donor bacteremia (asymptomatic at time of donation) - Skin flora introduced during phlebotomy - Environmental contamination during processing

Risk varies by product: - Platelets: Highest risk (stored at room temperature, which allows bacterial growth) - RBCs: Lower risk (stored cold; but certain organisms like Yersinia grow at 4°C) - Plasma: Lowest risk (frozen)

Common organisms: - Platelets: Skin flora (Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Propionibacterium) and Gram-negatives - RBCs: Gram-negatives that grow at cold temperatures-Yersinia enterocolitica (classic board answer), Serratia, Pseudomonas

Clinical Presentation

- High fever (often >39°C)

- Rigors

- Hypotension (may be severe, septic shock)

- Tachycardia

- May have nausea, vomiting

- Symptoms often begin during or immediately after transfusion

Workup and Management

- Stop transfusion

- Blood cultures from patient AND from the product bag

- Gram stain of product

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics immediately (don’t wait for culture results)

- Supportive care for sepsis

Prevention

- Diversion pouches: First 30-40 mL of collection (most likely to contain skin flora) is diverted into a separate pouch not used for transfusion

- Bacterial testing of platelets: Culture-based or rapid detection methods

- Visual inspection of products before transfusion (discoloration, clumps, hemolysis)

- Limiting platelet storage duration

- Pathogen reduction technology: Treats platelets with UV light and photosensitizers to inactivate bacteria (and viruses)

4.9 Post-Transfusion Purpura (PTP)

The Mechanism

PTP is a rare but severe reaction occurring 5-12 days after transfusion, characterized by sudden, profound thrombocytopenia.

The patient (usually a multiparous woman or previously transfused individual) has antibodies to a platelet-specific antigen they lack-most commonly HPA-1a (formerly PlA1).

The paradox: The patient’s own platelets are HPA-1a negative, so why do they get destroyed?

Several theories: - Innocent bystander: Soluble HPA-1a antigen in transfused plasma adsorbs onto recipient platelets, which are then destroyed by anti-HPA-1a - Cross-reactive antibodies: Anti-HPA-1a somehow cross-reacts with an epitope on HPA-1a negative platelets - Autoantibody induction: Exposure triggers an autoantibody

Clinical Presentation

- Severe thrombocytopenia (often <10,000/μL)

- Purpura, petechiae

- May have mucosal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage

- Self-limited (usually resolves in 1-4 weeks if patient survives)

Diagnosis

- Platelet-specific antibodies detected (anti-HPA-1a most common)

- Patient’s own platelets type negative for the corresponding antigen

Management

- High-dose IVIG (first-line; usually effective within days)

- Plasma exchange (if IVIG fails)

- Platelet transfusions are generally ineffective (transfused platelets are also destroyed)

- HPA-1a negative platelets may be tried if available

Chapter 5: Hemolytic Disease of the Fetus and Newborn (HDFN)

5.1 The Pathophysiology

HDFN occurs when maternal IgG alloantibodies cross the placenta and destroy fetal red blood cells. This requires:

- The mother is alloimmunized (has IgG antibodies to a red cell antigen she lacks)

- The fetus inherits the corresponding antigen from the father

- The maternal IgG crosses the placenta (IgG is the only immunoglobulin class that crosses; IgM does not)

- Maternal antibody binds fetal red cells

- Antibody-coated fetal red cells are destroyed (primarily in the fetal spleen)

The consequences depend on severity: - Mild: Hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy - Moderate: Significant anemia, hydrops fetalis (extramedullary hematopoiesis causes hepatosplenomegaly; severe anemia causes high-output cardiac failure) - Severe: Fetal or neonatal death

5.2 Causes of HDFN

Anti-D (Rh HDFN)

Before RhIG prophylaxis, anti-D was the leading cause of severe HDFN, causing thousands of fetal and neonatal deaths annually.

Why D is so problematic: - Highly immunogenic (80% of D-negative individuals exposed to D-positive blood make anti-D) - Approximately 15% of Caucasians are D-negative, so mismatched pregnancies are common - Anti-D is almost always IgG

With RhIG prophylaxis, Rh HDFN has become rare, but still occurs when: - RhIG is not given or is given inadequately - Massive fetomaternal hemorrhage exceeds RhIG coverage - Alloimmunization occurred before RhIG was available

Anti-K (Kell HDFN)

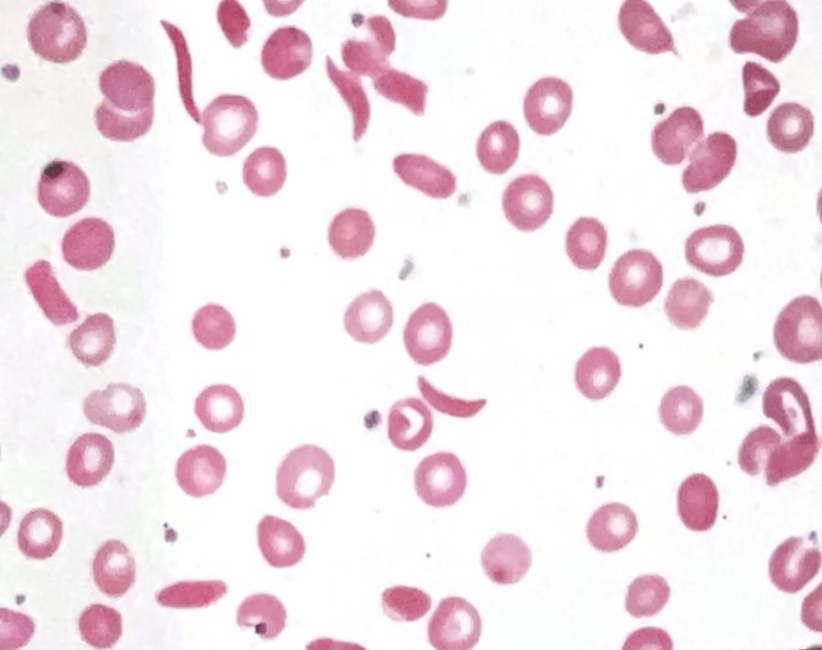

Anti-K causes HDFN by a unique mechanism: in addition to hemolysis, anti-K suppresses fetal erythropoiesis. This is because Kell antigen is expressed on early erythroid progenitors.

Implications: - Anemia may be more severe than predicted by antibody titer or bilirubin - Reticulocyte count may be inappropriately low - Amniocentesis for bilirubin (ΔOD450) underestimates severity

Other Antibodies

- Anti-c: Can cause severe HDFN; second most common cause after anti-D

- Anti-E: Usually causes mild HDFN

- Anti-Fya, anti-Fyb: Can cause moderate HDFN

- Anti-Jka, anti-Jkb: Usually mild if any HDFN

ABO HDFN

ABO incompatibility between mother and fetus is very common (about 20% of pregnancies), but ABO HDFN is usually mild because: - A and B antigens are not fully developed on fetal red cells - Anti-A and anti-B are mostly IgM (don’t cross placenta); the IgG component is relatively weak - A and B antigens are widely distributed in tissues (not just red cells), so antibody is “absorbed” by other tissues

ABO HDFN: - Most common cause of HDFN overall (but most cases are mild) - Typically presents as neonatal jaundice requiring phototherapy - Rarely requires exchange transfusion - Can occur in the first pregnancy (unlike Rh HDFN, which usually requires prior sensitization) - DAT may be only weakly positive or negative (low antibody density on cells)

5.3 Prevention of Rh HDFN: RhIG

Rh immune globulin (RhIG) is one of the great success stories of modern medicine. It prevents Rh sensitization through a mechanism called antibody-mediated immune suppression-when passively administered anti-D coats fetal D-positive cells in the maternal circulation, those cells are cleared before they can stimulate the maternal immune system.

Timing of Administration

Antepartum (routine): - At 28 weeks gestation (covers the period when fetomaternal hemorrhage becomes more common)

Postpartum: - Within 72 hours of delivery of a D-positive or D-unknown infant - Can be given up to 28 days with some benefit, though earlier is better

After sensitizing events: - Amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling - Abdominal trauma - External cephalic version - Miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, abortion - Antepartum hemorrhage

Dosing

Standard dose: 300 μg (1500 IU) of RhIG

This covers approximately 15 mL of fetal red cells (30 mL of whole blood).

For larger fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH), additional doses are needed.

Quantifying Fetomaternal Hemorrhage

Rosette test: Qualitative screen for FMH >10 mL fetal red cells. Uses anti-D to agglutinate D-positive fetal cells among D-negative maternal cells, forming rosettes around indicator D-positive cells.

If rosette screen is positive, quantify with:

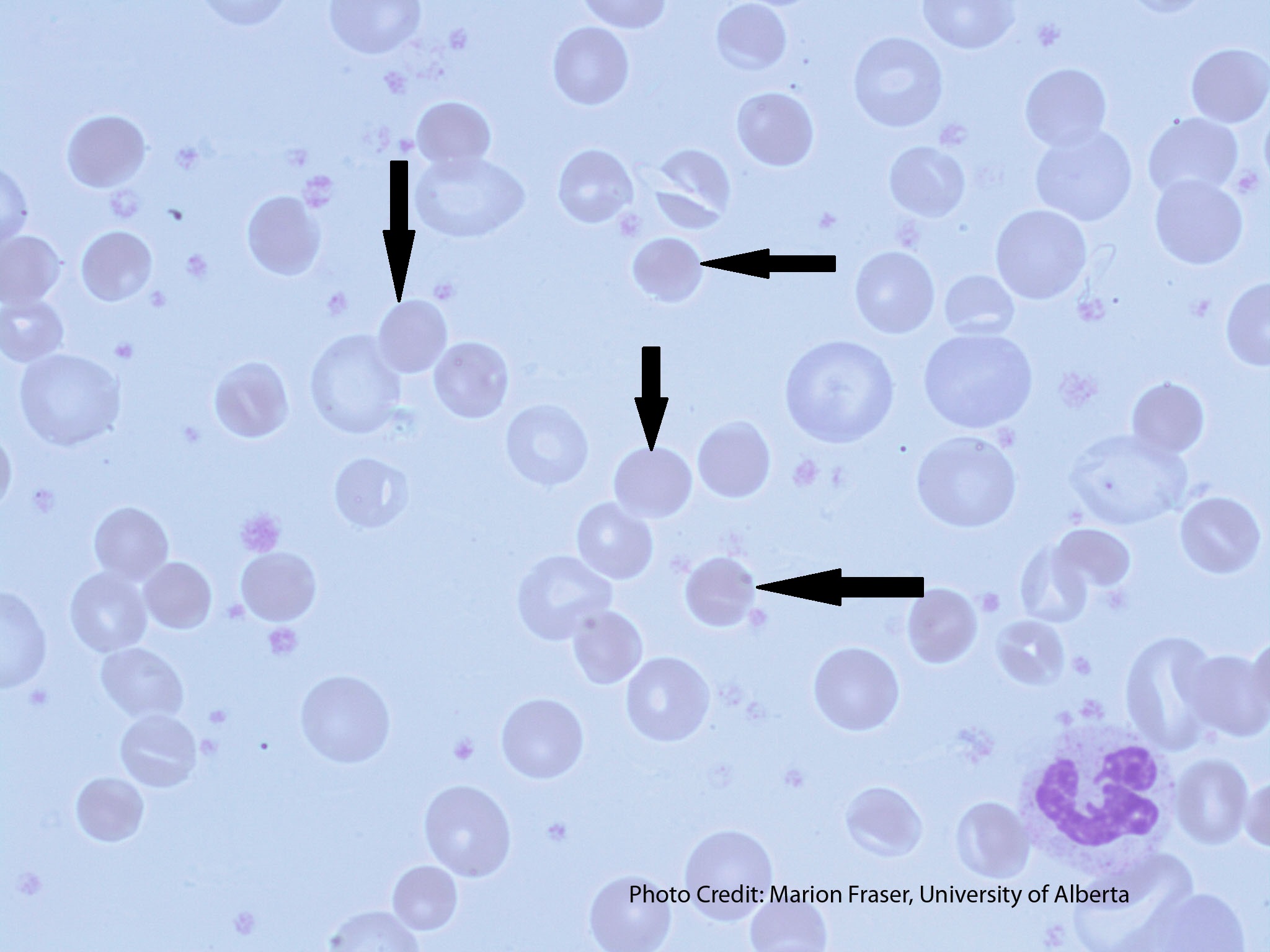

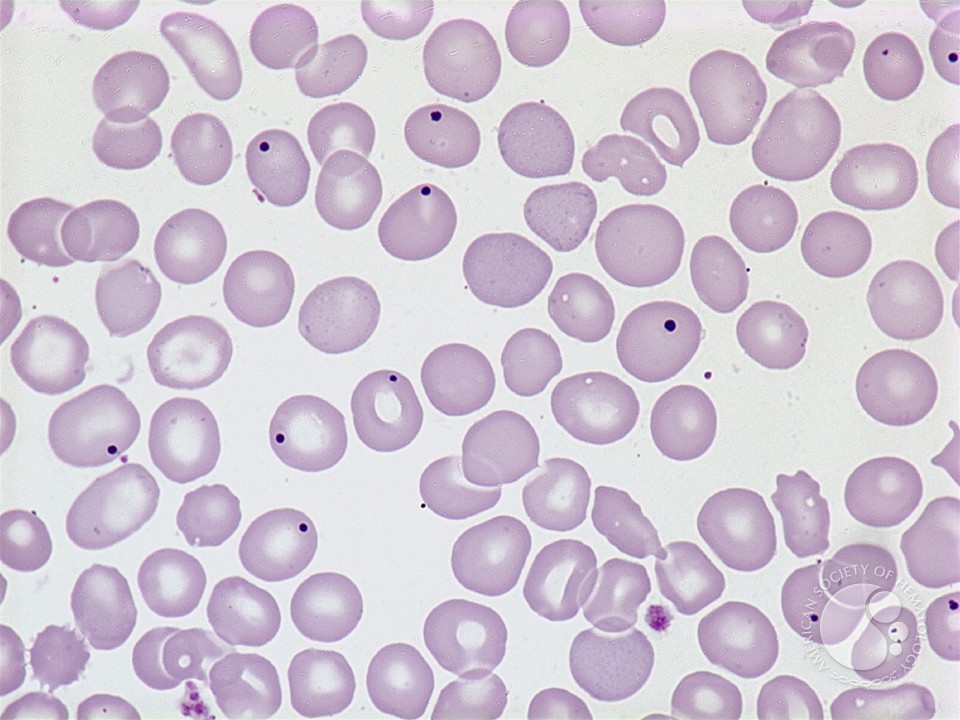

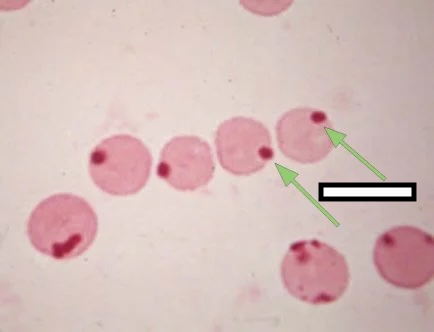

Kleihauer-Betke (acid elution) test: Based on the principle that fetal hemoglobin (HbF) is resistant to acid elution, while adult hemoglobin (HbA) is not. - A maternal blood smear is treated with acid - Adult RBCs appear as “ghosts” (hemoglobin washed out) - Fetal RBCs remain pink (HbF retained) - Count fetal cells per maternal cells and calculate: - % fetal cells × maternal blood volume = volume of fetal blood - Divide by 30 mL to get number of RhIG doses needed

Flow cytometry: More precise method using anti-HbF antibodies. Increasingly used for FMH quantification.

5.4 Management of the Alloimmunized Pregnancy

Antibody Monitoring

Once alloimmunization is detected: - Determine antibody specificity and titer - Determine the father’s antigen status and zygosity (is the fetus at risk?) - If father is antigen-negative: Fetus is not at risk - If father is homozygous positive: Fetus is definitely at risk - If father is heterozygous: 50% chance fetus is at risk → consider fetal testing - Cell-free fetal DNA testing can determine fetal antigen status from maternal blood

Titer Monitoring

If the fetus is at risk: - Monitor antibody titers every 2-4 weeks - “Critical titer” (varies by laboratory, typically 16-32): Above this level, significant HDFN is possible - Below critical titer: Continue monitoring - At or above critical titer: Move to MCA Doppler monitoring

Fetal Monitoring

Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) Doppler: Non-invasive assessment of fetal anemia - In anemic fetuses, cardiac output increases (to compensate) and blood viscosity decreases, resulting in increased blood flow velocity - MCA peak systolic velocity >1.5 MoM (multiples of the median for gestational age) suggests moderate to severe anemia - Serial MCA Doppler measurements guide decision-making about intervention

Amniocentesis: Historical method using ΔOD450 (optical density deviation at 450nm, indicating bilirubin level). Now largely replaced by MCA Doppler.

Fetal Intervention

Intrauterine transfusion (IUT): Direct transfusion of red cells to the fetus - Usually intravascular (into umbilical vein under ultrasound guidance) - Uses O-negative (or antigen-negative), irradiated, CMV-safe, leukoreduced, fresh RBCs - Hematocrit targeted to be high (80-85%) since volume is limited - May need to be repeated every 1-3 weeks until delivery

5.5 Neonatal Management

Assessment at Birth

- Cord blood: ABO/Rh type, DAT, hemoglobin/hematocrit, bilirubin

- Evaluate for hydrops (edema, ascites, pleural effusions)

Treatment of Hyperbilirubinemia

Phototherapy: First-line treatment - Blue light (wavelength 460-490 nm) converts unconjugated bilirubin to water-soluble photoisomers that can be excreted without conjugation - Threshold for treatment depends on gestational age, age in hours, and risk factors

Exchange transfusion: For severe cases unresponsive to phototherapy, or when bilirubin levels approach dangerous thresholds - Removes antibody-coated red cells, free antibody, and bilirubin - Replaces with antigen-negative, compatible red cells - Usually “double volume exchange” (twice the infant’s blood volume, ~170 mL/kg) - Uses O-negative (or specifically antigen-negative), irradiated, CMV-safe red cells

IVIG: May reduce need for exchange transfusion by blocking Fc receptors on macrophages, reducing hemolysis

5.6 Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia (NAIT)

NAIT is the platelet equivalent of HDFN-maternal antibodies against fetal platelet antigens cause fetal/neonatal thrombocytopenia. However, there are critical differences that make NAIT more dangerous in some ways.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism parallels HDFN: 1. The fetus inherits a platelet antigen from the father that the mother lacks 2. Fetomaternal hemorrhage exposes the mother to fetal platelets 3. The mother develops IgG antibodies against the foreign platelet antigen 4. Maternal IgG crosses the placenta and destroys fetal platelets

The critical difference from HDFN: NAIT often affects the FIRST pregnancy. Unlike Rh HDFN, which requires prior sensitization, the amount of fetal platelets reaching maternal circulation during pregnancy is sufficient to cause sensitization and antibody production within the same pregnancy. About 50% of NAIT cases occur in first pregnancies.

The HPA System

Human Platelet Antigens (HPAs) are polymorphisms in platelet membrane glycoproteins. The most important are:

| Antigen | Glycoprotein | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| HPA-1a (PlA1) | GPIIIa (integrin β3) | Causes ~80% of NAIT cases |

| HPA-1b (PlA2) | GPIIIa | Antithetical to HPA-1a |

| HPA-5b (Bra) | GPIa (integrin α2) | Second most common cause |

| HPA-3a | GPIIb | Less common |

| HPA-4a | GPIIIa | Rare |

HPA-1a incompatibility is the classic scenario: - Mother is HPA-1a negative (HPA-1b/1b)-about 2% of Caucasians - Father is HPA-1a positive - Fetus inherits HPA-1a from father - Mother makes anti-HPA-1a

Clinical Presentation

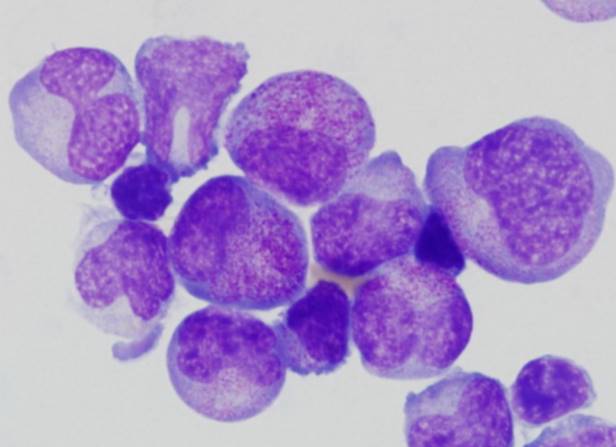

Fetal/neonatal thrombocytopenia: Can be severe (<20,000/μL)

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH): The devastating complication - Occurs in 10-20% of NAIT cases with severe thrombocytopenia - Can occur in utero (unlike HDFN, where severe anemia is the main fetal risk) - Leads to death or permanent neurological damage - ICH can occur as early as 16-20 weeks gestation

Petechiae, purpura, bleeding: At birth

Unlike HDFN: There is no readily available screening test or prophylaxis equivalent to RhIG. NAIT is usually diagnosed AFTER an affected baby is born.

Diagnosis

Clinical suspicion: Unexplained neonatal thrombocytopenia, especially if severe and in an otherwise healthy full-term infant

Laboratory confirmation: - Maternal platelet antigen typing (HPA genotyping) - Paternal platelet antigen typing - Detection of maternal anti-platelet antibodies (MAIPA-monoclonal antibody immobilization of platelet antigens) - Confirmation of incompatibility between maternal and fetal platelet types

Differential diagnosis: - Neonatal sepsis - Congenital infection (TORCH) - Maternal ITP (autoantibodies, not alloantibodies; affects mother too) - Congenital thrombocytopenia syndromes

Management

Affected neonate: - Platelet transfusion: Ideally with HPA-compatible platelets (antigen-negative for the implicated antigen) - If HPA-typed platelets unavailable, random donor platelets may provide partial, temporary increment - Maternal platelets can be washed (to remove antibody-containing plasma) and irradiated-they lack the offending antigen - IVIG: May raise platelet count by blocking Fc receptors on macrophages

Subsequent pregnancies (recurrence risk 75-90% with 50% chance of more severe disease): - Fetal blood sampling to monitor platelet count (high-risk procedure) - Maternal IVIG during pregnancy (may improve fetal platelet count) - Intrauterine platelet transfusions if severe thrombocytopenia - Early delivery if severe, to enable postnatal treatment - Cesarean section may be recommended to avoid birth trauma if platelet count is very low

Key Differences: NAIT vs. HDFN

| Feature | NAIT | HDFN |

|---|---|---|

| Target cells | Platelets | Red blood cells |

| Most common antibody | Anti-HPA-1a | Anti-D |

| First pregnancy affected | Yes (~50%) | Rarely (requires prior sensitization) |

| In utero bleeding risk | High (ICH) | Low |

| Prophylaxis available | No | Yes (RhIG) |

| Screening | Not routine | Routine (blood type) |

| Severity in subsequent pregnancies | Often worse | Often worse |

Chapter 6: Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA)

Before discussing the specific types of AIHA, it’s essential to understand how to distinguish intravascular from extravascular hemolysis in the laboratory-a distinction that has direct clinical implications.

Laboratory Differentiation of Hemolysis Types

| Finding | Intravascular Hemolysis | Extravascular Hemolysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary site | Bloodstream (complement-mediated) | Spleen/liver (RES macrophages) |

| Haptoglobin | ↓↓ (absent-saturated by free Hgb) | ↓ (moderate decrease) |

| LDH | ↑↑ (marked elevation) | ↑ (moderate elevation) |

| Indirect bilirubin | ↑ | ↑ |

| Hemoglobinemia | Present (pink/red plasma) | Absent |

| Hemoglobinuria | Present (dark urine, + blood dipstick, no RBCs) | Absent |

| Hemosiderinuria | Present (late finding) | Absent |

| Spherocytes | Variable | Often present (from partial phagocytosis) |

Clinical correlation: Intravascular hemolysis releases free hemoglobin directly into plasma, which saturates haptoglobin (causing it to disappear), is filtered by kidneys (hemoglobinuria), and can cause renal tubular injury. Extravascular hemolysis occurs when macrophages remove antibody-coated or damaged cells intact; the hemoglobin is metabolized inside cells to bilirubin, never reaching plasma as free hemoglobin.

6.1 Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

Pathophysiology

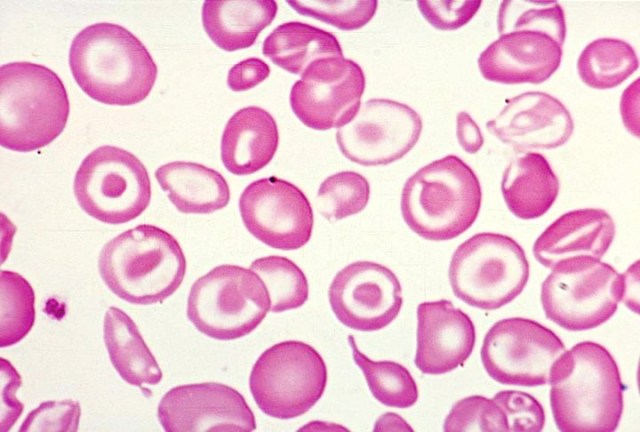

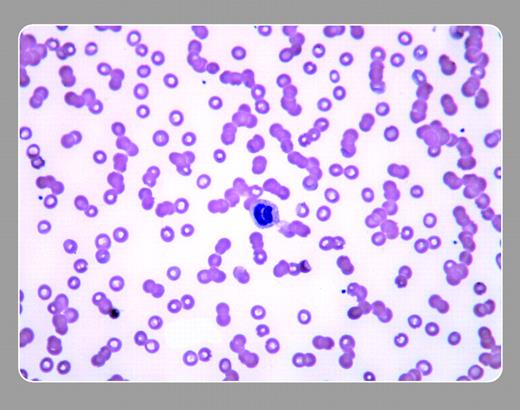

In warm AIHA, the patient’s immune system produces IgG autoantibodies that bind to their own red blood cells at body temperature (37°C). These antibody-coated red cells are recognized by Fcγ receptors on splenic macrophages and destroyed-primarily through partial phagocytosis, which creates spherocytes.

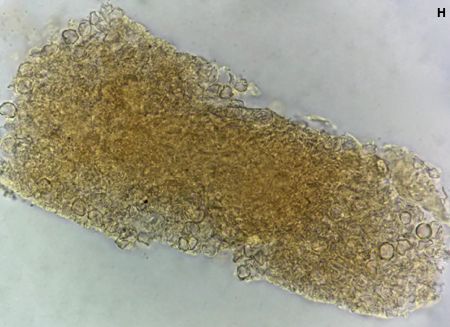

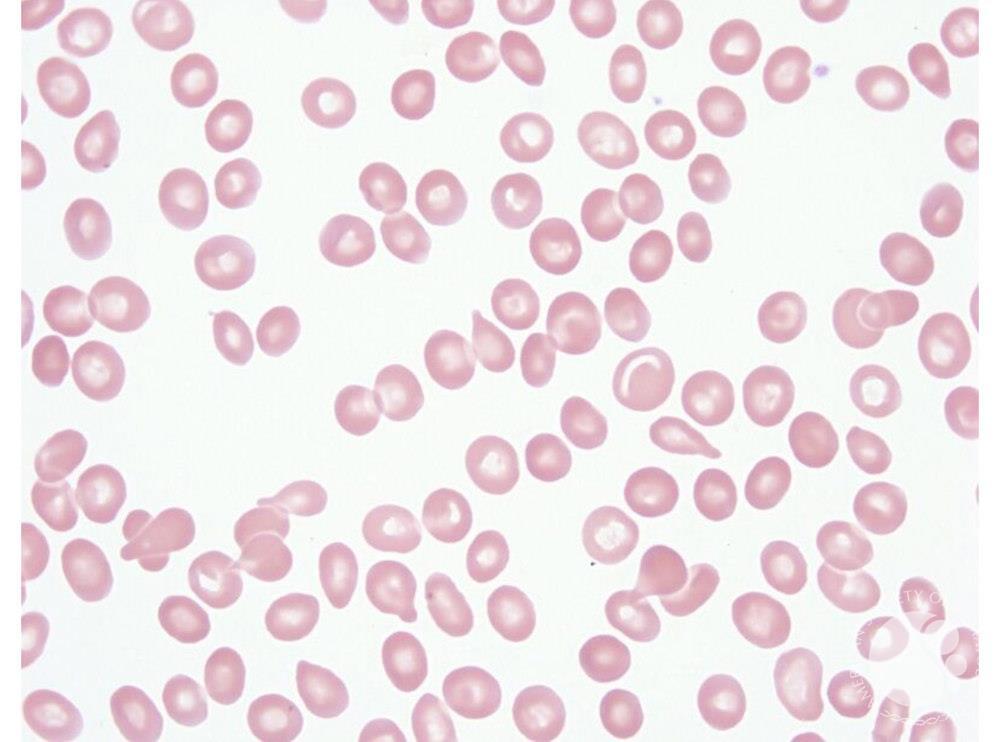

Why are spherocytes formed? When a macrophage “bites” a piece of antibody-coated red cell membrane but the cell escapes, the remaining cell has reduced surface area but the same volume. It becomes spherical-the shape with the lowest surface area-to-volume ratio. These spherocytes are rigid and become trapped in the splenic cords, leading to further destruction.

Causes

- Primary (idiopathic): ~50% of cases; no underlying cause identified

- Secondary:

- Lymphoproliferative disorders (CLL, lymphoma)

- Autoimmune diseases (SLE, rheumatoid arthritis)

- Drugs (methyldopa, fludarabine)

- Infections

Laboratory Findings

- Evidence of hemolysis: ↓ Hgb, ↑ reticulocytes, ↑ LDH, ↑ indirect bilirubin, ↓ haptoglobin

- Spherocytes on peripheral smear

- DAT positive: Usually IgG positive (±C3)

- Antibody screen and panel may be positive (autoantibody reacts with all cells)

Blood Bank Challenges

Finding compatible blood for warm AIHA patients can be difficult: - Autoantibody may react with all cells in the antibody screen - Must rule out underlying alloantibodies (patients with AIHA often have alloantibodies from prior transfusions) - Use autoadsorption or alloadsorption to remove autoantibody and unmask alloantibodies

Autoadsorption: Patient’s own cells (warmed to elute autoantibody, then used to adsorb remaining autoantibody from serum). Cannot be used if patient was recently transfused.

Alloadsorption: R1R1, R2R2, and rr cells used to adsorb autoantibody while preserving alloantibodies of those specificities.

Treatment

- Corticosteroids: First-line; prednisone 1-1.5 mg/kg/day

- Rituximab: Anti-CD20; often second-line

- Splenectomy: Removes primary site of red cell destruction

- Immunosuppressants: Azathioprine, mycophenolate, etc.

- Transfusion: When needed, give “least incompatible” blood; don’t withhold blood for life-threatening anemia because you can’t find compatible blood

6.2 Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD)

Pathophysiology

In CAD, the patient has IgM autoantibodies (cold agglutinins) that bind to red cells at temperatures below body temperature. The classic antibody is anti-I, which binds to the I antigen (a carbohydrate structure on adult red cells).

The mechanism of hemolysis: 1. Blood flows through cool peripheral tissues (fingers, toes, ears, nose) 2. IgM binds to red cells in the cold and activates complement (C1 through C3) 3. Blood returns to warm central circulation; IgM dissociates (poor binding at 37°C) 4. Complement activation stops at C3b (regulatory proteins prevent progression to MAC) 5. C3b-coated red cells are recognized by complement receptors on hepatic macrophages 6. Red cells are destroyed in the liver (extravascular hemolysis) or converted to spherocytes 7. Some intravascular hemolysis occurs if complement proceeds to C5-9

Causes

- Primary: Clonal B-cell disorder producing monoclonal IgM cold agglutinin

- Secondary:

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection (produces anti-I; typically polyclonal, transient)

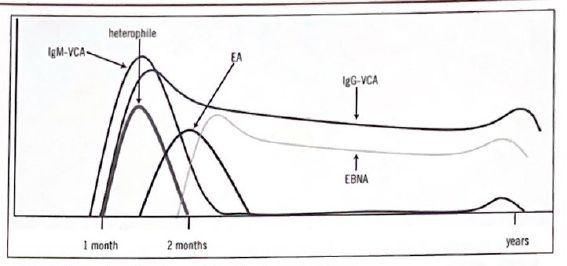

- EBV infection (may produce anti-i, targeting fetal-type antigen)

- Lymphoproliferative disorders

Laboratory Findings

- DAT: C3d positive, IgG negative (IgM dissociates during washing)

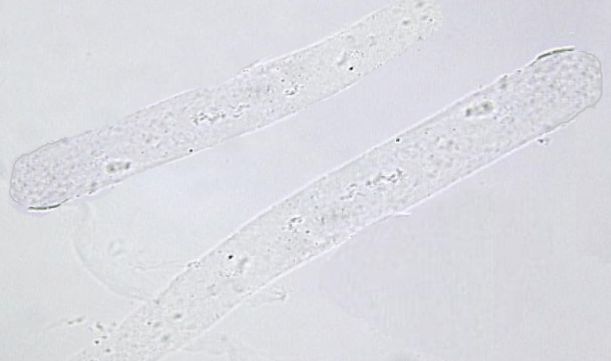

- May see red cell agglutination at room temperature (must warm sample to get accurate CBC)

- Cold agglutinin titer (significant if ≥64 at 4°C)

- Thermal amplitude (temperature range of reactivity) determines clinical significance-wider amplitude = worse disease

Blood Bank Challenges

Cold agglutinins interfere with testing: - May cause ABO discrepancies (agglutination in reverse typing) - May cause positive antibody screen at room temperature

Solutions: - Keep samples warm (37°C) - Pre-warm technique for crossmatching - Identify underlying alloantibodies using pre-warmed or enzyme-treated cells

Treatment

- Avoid cold exposure (most important)

- Corticosteroids are usually ineffective

- Rituximab (targets the B-cell clone)

- Splenectomy is not helpful (destruction is primarily hepatic)

- Complement inhibitors (sutimlimab) recently approved

- Transfuse through blood warmer if needed

6.3 Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria (PCH)

Pathophysiology

PCH is caused by the Donath-Landsteiner antibody, an unusual IgG that binds red cells at cold temperatures, fixes complement, and causes intravascular hemolysis when blood warms.

The antibody has anti-P specificity (reacts with P antigen, present on nearly everyone’s red cells).

The biphasic nature: 1. In cold (peripheral circulation): IgG antibody binds red cells and fixes complement through C3 2. Blood warms (central circulation): Complement cascade proceeds to MAC, causing intravascular hemolysis

Why doesn’t the IgG stay bound? The Donath-Landsteiner antibody has very low affinity at warm temperatures and rapidly dissociates.

Clinical Context

PCH occurs in two settings: 1. Children following viral infections (most cases today)-typically self-limited 2. Adults with syphilis (historical association; rare today)

Laboratory Findings

- DAT: C3d positive only (similar to CAD)

- Donath-Landsteiner test: Demonstrates biphasic hemolysis

- Incubate patient serum with red cells at 4°C (antibody binds, fixes complement)

- Warm to 37°C (lysis occurs)

- Control tubes at only 4°C or only 37°C do not lyse

Treatment

- Usually supportive; self-limited in children

- Keep patient warm

- Transfusion if needed (difficult to find P-negative blood; use standard compatible blood through warmer)

6.4 Drug-Induced Hemolytic Anemia

Drugs can cause a positive DAT and hemolytic anemia through several mechanisms:

Drug Adsorption (Hapten) Mechanism

- Classic example: Penicillin

- Drug binds tightly to red cell membrane

- Antibody is directed against the drug (not the red cell)

- Only drug-coated cells are destroyed

- DAT: IgG positive

- Requires high-dose drug therapy

- Resolves when drug is stopped

Immune Complex (Innocent Bystander) Mechanism

- Examples: Quinidine, quinine, certain NSAIDs

- Drug-antibody immune complexes form in plasma

- Complexes bind to red cells and activate complement

- DAT: Usually C3 positive (IgG may be positive too)

- Can cause severe intravascular hemolysis

- Low drug doses can trigger reaction

Autoantibody Induction

- Classic example: Methyldopa (also fludarabine, procainamide)

- Drug induces true autoantibodies (not drug-dependent)

- Autoantibodies react with red cells even without drug present

- DAT: IgG positive

- Mechanism unknown (possibly alteration of self-antigens or immune dysregulation)

- Hemolysis may persist after drug is stopped (autoantibodies take time to disappear)

Membrane Modification (Non-immune)

- Examples: Cephalosporins

- Drug modifies red cell membrane to nonspecifically adsorb proteins (including immunoglobulins)

- DAT: May be positive for IgG and/or C3

- No true antibody-mediated hemolysis

- Positive DAT without hemolysis

Chapter 7: Apheresis

7.1 Principles of Apheresis

Apheresis (from Greek “to take away”) refers to procedures that separate blood components, removing one component while returning the rest to the patient/donor.

Separation Technologies

Centrifugation-based: Most common. Blood flows into a spinning bowl or channel where components separate by density: - Plasma (least dense, innermost layer) - Platelets and buffy coat (middle) - Red cells (most dense, outermost layer)

Membrane filtration: Used for plasmapheresis. Plasma passes through a membrane while cells are retained.

7.2 Therapeutic Apheresis

Therapeutic Plasma Exchange (TPE)

In TPE, the patient’s plasma is removed and replaced with a replacement fluid (albumin solution or FFP).

Mechanism of action: Removes pathogenic substances from the plasma: - Autoantibodies - Alloantibodies - Immune complexes - Paraproteins - Toxins bound to plasma proteins

Kinetics: Each plasma volume exchange removes approximately 63% of an intravascular substance. After 1-1.5 plasma volumes: - First exchange: Removes ~63% - Second exchange: Removes 63% of remaining → total 86% - Third exchange: → total 95%

However, substances re-equilibrate from extravascular space, so serial exchanges are needed.

Replacement fluids: - Albumin (5%): Preferred in most cases. Doesn’t transmit infection. Doesn’t replace coagulation factors (may need FFP if patient is bleeding or before invasive procedures). - FFP: Required for TTP (provides ADAMTS13). Used when coagulation factor replacement is needed.

Indications (ASFA Category I-first-line treatment): - TTP (Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura): Removes anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies, provides functional ADAMTS13 - Myasthenia gravis (acute exacerbation): Removes anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies - Guillain-Barré syndrome: Removes pathogenic antibodies - ANCA-associated vasculitis (severe): Removes ANCA - Anti-GBM disease (Goodpasture): Removes anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies - Hyperviscosity syndrome: Rapidly reduces paraprotein levels

Complications: - Citrate toxicity (hypocalcemia): Citrate used as anticoagulant binds calcium. Symptoms include paresthesias, muscle cramps, and in severe cases, arrhythmias. Treat with calcium supplementation. - Hypotension: From volume shifts. More common with FFP replacement (allergic reactions). - Coagulopathy: Removal of clotting factors (if albumin replacement used) - Allergic reactions: Especially with FFP - Line complications: Infection, thrombosis, pneumothorax

Cytapheresis Procedures

Leukapheresis: Removal of white blood cells - Indication: Hyperleukocytosis in leukemia (WBC >100,000/μL with symptoms) - Goal: Rapidly reduce WBC count while definitive chemotherapy takes effect - Symptomatic relief of leukostasis (pulmonary, neurologic)

Plateletpheresis: Removal of platelets - Indication: Symptomatic thrombocytosis (usually platelets >1 million with ischemic symptoms) - Provides temporary reduction while medications take effect

Erythrocytapheresis (Red Cell Exchange): Removal of patient’s red cells and replacement with donor red cells - Sickle cell disease: Rapidly reduces HbS percentage; first-line for acute chest syndrome, stroke - Severe malaria: Reduces parasitemia rapidly - Polycythemia vera: Alternative to phlebotomy

Photopheresis (Extracorporeal Photochemotherapy): - White cells are collected, treated with psoralen (photosensitizing agent) and UVA light, then returned - Mechanism: Induces apoptosis of treated lymphocytes, modulates immune response - Indications: Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome), chronic GVHD, solid organ transplant rejection

Chapter 8: Special Clinical Situations in Transfusion Medicine

8.1 Massive Transfusion

Definition: Replacement of one or more blood volumes within 24 hours (approximately 10 units of RBCs in a 70 kg adult), or transfusion of more than 4 units in one hour with ongoing bleeding.

The Pathophysiology of Coagulopathy in Massive Hemorrhage

Massive hemorrhage creates a “deadly triad” that drives coagulopathy:

Hypothermia: Blood stored at 4°C, large-volume cold crystalloid resuscitation, and exposed body cavities all lower core temperature. At 34°C, enzymatic activity of coagulation factors is reduced by ~25%; at 32°C, by ~50%. Hypothermia also impairs platelet function.

Acidosis: Tissue hypoperfusion leads to anaerobic metabolism and lactic acidosis. At pH 7.2, the activity of the Xa/Va prothrombinase complex is reduced by 50%; at pH 7.0, by 70%.

Dilution: Resuscitation with crystalloids and RBCs (which contain no plasma or platelets) dilutes the patient’s remaining clotting factors and platelets. After replacement of one blood volume (~10 units RBCs), only ~35% of original plasma and platelets remain.

These three factors compound each other-hypothermia worsens acidosis, acidosis impairs clotting, and dilution exacerbates both problems.

Trauma-induced coagulopathy: In trauma patients, coagulopathy often begins before resuscitation, driven by tissue injury, shock, and activation of the protein C pathway. This “acute coagulopathy of trauma” causes fibrinolysis and factor depletion independent of dilution.

Massive Transfusion Protocols (MTP)

Modern MTPs aim to replace blood components in ratios approximating whole blood, preventing dilutional coagulopathy:

Ratio-based approach: - Typical ratios: 1:1:1 (RBC:FFP:platelets in units) or 1:1:2 - The PROPPR trial (JAMA 2015) found 1:1:1 achieved hemostasis faster than 1:1:2, with trends toward improved survival - Practical implementation: After every 4-6 units of RBCs, give 4-6 units of plasma and 1 apheresis platelet dose

Goal-directed approach (when labs are available): - Hematocrit <30%: Transfuse RBCs - INR >1.5 or aPTT >1.5× normal: Transfuse FFP (10-15 mL/kg) - Platelets <50,000/μL: Transfuse platelets - Fibrinogen <100-150 mg/dL: Transfuse cryoprecipitate (10 units)